Poker & Pop Culture: Playing Cards with Paul Newman

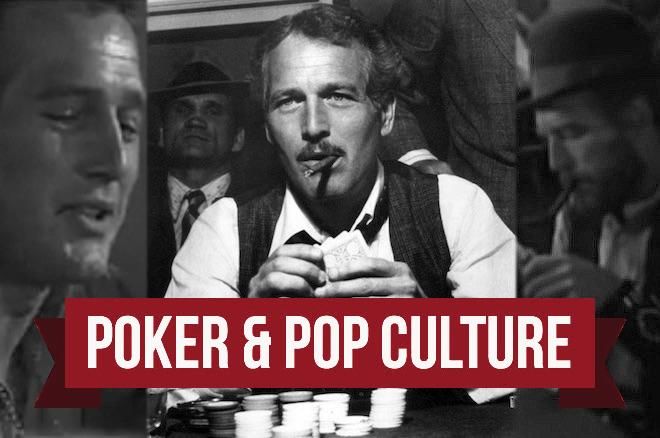

When we think of poker in film, it is hard not to think of Paul Newman.

Whether as prisoner Luke Jackson, repeatedly calling out to "kick a buck" with nothing but air in Cool Hand Luke (1967), or as con man Henry Gondorff surprisingly turning over quad jacks to outcheat a cheater in The Sting (1973), Newman's grinning mug necessarily springs to mind whenever someone sets out to compile a short list of the silver screen's best poker scenes.

By the time of his passing in 2008, Newman had appeared in over 60 films, with America's favorite card game popping up in more than a few of them. As a result, Newman came to be identified somewhat with the game.

In fact, among the many quotes often attributed to the actor is a poker-related one which anyone reading this article will undoubtedly recognize:

"If you're playing a poker game and you look around the table and can't tell who the sucker is, it's you."

So Newman is thought to have said, although the line likely had its origins elsewhere. Whatever its true source, it's a line fans of poker films recognize instantly as paraphrased by Mike McDermott during the opening of Rounders (1998): "If you can't spot the sucker in the first half-hour at the table, then you are the sucker."

The actor was himself not an especially dedicated poker player, at least not according to his biographer Shawn Levy. "Despite the evidence of his film work," writes Levy, "he played pool and poker passingly to badly; chess too." When it came to card games, Newman preferred bridge instead, says Levy, spending down time on sets "working out bridge hands silently in his head."

On the screen, though, poker was the game Newman's characters most often played, with those aforementioned poker scenes from Cool Hand Luke and The Sting easily the most memorable.

As the stubborn, intrepid inmate in Cool Hand Luke, it's a game of five-card stud that helps Newman's Luke earn a certain status among the other prisoners, as well as his nickname.

In the hand, several disinterested-and-thus-super-strong-appearing raises from Luke ultimately force his opponent to fold his "pair of Savannahs" (or sevens), at which point Luke reveals his king-high. Or, as observer Dragline (George Kennedy) gleefully crows, "a hand full of nothing."

"Yeah, well," says Luke, pausing just a beat while opening a bottle, "sometimes nothing can be a real cool hand." In just three minutes, Luke's complicated character is comprehensively defined both to the other prisoners and to the audience via a simple hand of poker.

The Sting found Newman teamed with Robert Redford as a pair of Depression-era grifters out to score revenge on a large scale against a hated crime boss named Lonnegan. Along the way, the twisty, surprise-filled plot places Newman's Gondorff on a cross-country train across the poker table from their enemy in a private, high-stakes game.

Playing five-card draw, the villain Lonnegan has a deck prepared to ensure Gondorff receives quad treys versus his own four nines. But Gondorff has an extra deck himself from which to draw cards, and when the betting concludes, he is the one who surprisingly turns over the best hand �� four jacks �� to the disbelief of Lonnegan.

"What was I supposed to do?" says a fuming Lonnegan afterwards. "Call him for cheating better than me in front of the others?"

Choosing among other Newman films in which poker makes a meaningful appearance, there are also Hud (1963), The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972) and Nobody's Fool (1994).

Adapted from Larry McMurtry's novel, Hud finds Newman as the irascible title character, a woman-chasing man in his mid-30s growing increasingly uncomfortable with a life working on his father's cattle farm.

A family drama in which Newman plays an antagonist pitted against his father and nephew, relationships are further complicated by the presence of their housekeeper, Alma, played by Patricia Neal in an Oscar-winning performance.

Midway through the film comes a sexually-charged meeting between Hud and Alma during which she explains how her ex-husband was a gambler whom she now suspects is probably working as a dealer in Reno or Las Vegas. In fact, Alma has just come from a poker game herself where she left a winner.

Hud asks her "how much you take the boys for tonight," her ability as a player clearly increasing his fascination with her.

While Newman doesn't play poker in Hud, he does in another western, The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972). Though loosely based on a true story, the strange, uneven film plays out like a fantasy with a sequence of strange episodes featuring Newman's eccentric Bean surrounded by a cast of oddballs.

As an outlaw Bean stops in a frontier town where he is robbed and nearly killed. He soon exacts bloody revenge, then appoints himself the "judge" of the town where he eventually surrounds himself with marshals, a mayor and others amenable to his idiosyncratic rule. In a sense, Bean is a Don Quixote-like figure, living in a world of his own imagination and successfully persuading others to do the same.

The judge frequently holds court over poker games, said by one of the marshals who narrates part of the story as having "had as much to do with winning the West as Colts .45 or the Prairie schooner." Indeed, poker is described as "more a religion, than a game," with Bean believing himself "a past master."

That said, the games shown in the film serve mainly to show Bean to be a losing player, though nonetheless confirm his authority over his dusty kingdom. For example, after losing a hand to one of his marshals, Whorehouse Lucky Jim, the Judge immediately charges him $25 for the next beer he orders.

"That ain't sportin'," complains Jim. "What is a man supposed to do?" "Start losing or quit drinking," declares Bean.

One last poker game precedes a final battle between Bean and a rival to his authority. As if to foreshadow the gunplay to come, the players use bullets for chips. "I open for a .38," says one. "I call the .38 and raise you two .45s."

It goes without saying that when the end comes for Bean his demise is reported thusly: "the judge cashed in his chips."

Finally, Newman again found himself at a poker table in Nobody's Fool (1994), a smart, occasionally moving film that deserves a wider audience. There Newman plays yet another against-the-grain type in Sully Sullivan, a freelance construction worker struggling to get by in wintry upstate New York.

Sully hates Carl Roebuck (Bruce Willis), owner of Tip Top Construction, but is forced to take work from him. The pair butt heads at the poker table, too, where Carl taunts Sully by calling him "the only guy I know still dumb enough to believe in luck." Sully has a response for a man who inherited his business from his father: "I used to believe in brains and hard work 'til I met you."

Whether by luck or otherwise, Carl beats Sully in their game, and appears to be beating him in life, too, having married the beautiful Toby (Melanie Griffith) �� with whom Sully openly flirts �� though Carl is cheating on her with a succession of secretaries.

Meanwhile, Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays force Sully to consider whether he ought to try to amend what has been a life as a neglectful father and grandfather, with the subsequent development of that primary plot providing both an absorbing story and opportunity for Newman to shine in a particularly well-fitting role.

Sully gets another crack at Carl in a later poker game, by which point his change in character has taken place. Things go better for him there, but when others mention his luck turning, he insists �� much like a knowledgeable poker player �� that "luck has nothing to do with it."

One more film of Newman's in which poker takes place, although only in passing, is The Hustler (1961). Even so, in his 1977 book of essays Total Poker, David Spanier provocatively suggests The Hustler to be "the best film about poker," even though "it isn't about poker at all."

Pointing out how the story of the pool-player Fast Eddie constitutes "probably the definitive statement about winning and losing in games, if not in life," Spanier believes the movie to provide cinema's most cogent commentary on poker without even focusing on the actual game.

"Although The Hustler is about pool, its lessons apply just as strongly, indeed precisely, to poker," argues Spanier.

Can't really blame Spanier too much for thinking of poker while watching a Paul Newman movie �� even one in which poker isn't being played. After all, the guy always seemed to have cards in his hand.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America's Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.