Betting Small When Strong to Induce Crying Calls (or Check-Raises)

It is not that rare to play against an opponent who is playing imperfectly in no-limit hold'em tournaments.

Occasionally you'll find yourself in a spot where, on the river, it seems like your opponent just can't call you. That is, your opponent has played the hand in a way where you're pretty sure he just isn't confident he has the best hand �� e.g., the board rolled out too scary, his range is too weak, and/or other factors are signaling as much.

It's a great spot if you yourself are weak and are bluffing, but what if you have a strong hand? How do you get chips from an opponent such as this?

The first skill in managing these spots is recognizing them. The second is picking a bet size that targets a range that feels it can never call. This is almost always a small size that might earn a crying call �� or, even better, induce a raise.

Here's a hand from a $50 full-ring no-limit hold'em freezeout illustrating an example of this type of hand, one in which we arrive at the river in just such a situation where we want to make the right-sized bet in order to encourage an imperfect response.

First Actions

At 25/50 blinds with a 6-chip ante, a recreational player limps in under the gun, and next to act an unknown player makes it 279, about 5.5 big blinds. We are next to act with A?Q? and have no choice but to call.

There are seven players left to act behind us and if any of them call they are likely to have a worse hand than ours, but if we reraise and any continue, we are likely to be the one playing catch up. Besides, there is value in our keeping the UTG limper in the pot and retaining our position against the raiser. We can bloat the pot later if it suits us (spoiler �� it will, and we will).

We call and it folds around to the limper who calls as well, making the pot 966. We have 5,050 left in our stack, the raiser covers us, and the limper has 4,500. The flop comes Q?3?3?.

The limper checks and the initial raiser continuation bets 319. We could raise. We have the best queen, we block A-A, and we have equity against K-K. Meanwhile the limper is unlikely to fold Q-J or K-Q even if we do raise, and the initial raiser may also continue and call us with T-T or J-J.

While raising has merits, it is probably best to call in this situation. We can get value from those hands we are ahead of later and the board is static �� that is, unlikely to change markedly. We retain the value of our position if we just call in position, but we may forsake it if we raise. Besides, if we call, the limper may come along with a hand that would have folded to a raise, like 5-5.

We call, and the limper indeed calls. The pot is now 1,923 going to the turn.

Setting Up a River Shove

The turn card is the 2?, giving us the nut flush draw to go with top pair, top kicker. It is also the least likely card to fill up our opponents' possible pocket pairs. What a wonderful card.

Action checks to us with 4,732 left in our stack. While it is difficult for both players to have a hand that can call a sizeable bet, it is probably most important at this stage in the hand to target worse QxXx hands �� e.g., K-Q and Q-J �� than to worry about milking weak pocket pairs like 8-8.

Betting 1,345 into 1,923 may seem large, but remember the big size our opponent raised before the flop, and from early position. That suggests a strong range that will likely be able to continue against this size often enough. Should we face a shove from either player, we will be forced to call with our hand.

The limper folds to this bet and the initial raiser calls. That means the preflop raiser has (1) raised large preflop, (2) continuation bet a Q-3-3 flop, and (3) check-called a largish bet on a blank turn. He must have something, but if that something was strong, he likely would have bet it himself again on the turn.

Reading the River

The river is the A?, making the final board Q?3?3?2?A? and giving us top two pair. Our opponent checks to us. The pot is 4,613 with 3,387 left in the effective stacks. Easy shove, right?

Not so fast. With what can our opponent call?

We hold the A?. That means he could not have check-called the turn with A?J?, A?10?, A?K?, A?4?, or A?5?. We have an ace and a queen, so we block hands like A-K and K-Q. Combination-wise it seems like we might have just drawn out on K-K, since our hand and the board does not block K-K at all. But his turn check-call makes that unlikely, as he could have either bet or check-raised the turn with kings.

When we are thinking through the possible hands, it is hard to say what, exactly, our opponent could even have. We are almost never beat here. We block A-A and Q-Q, and it is very difficult for our opponent to hold 5-4.

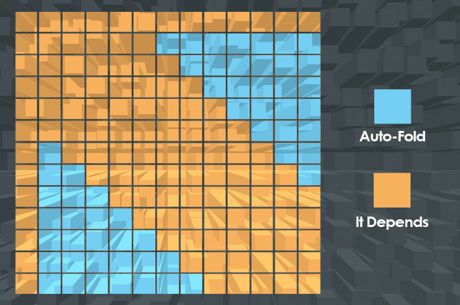

This is not a spot on an ace-high board where if we had A-K we can target A-Q, A-J, A-T, and so forth down the line. Because it is so hard to imagine our opponent having an ace (i.e., a hand that can call a river shove), a bet size choice here was made, betting 1,234 into 4,613, to elicit crying calls from QxXx. We could have even bet smaller.

In this case, instead of making that crying call, our opponent check-raised all in for 2,153 more. We called happily and were shown 10?10?. We win.

Target Weakness

Our opponent's range on the river was weak. Recognizing that was a process that began by keeping tabs on our opponent's range starting from his first action before the flop, namely the size he raised and from what position.

We could not pinpoint exactly what hand he had on the river. All we knew was that a range that might have been full of AxXx hand before the flop, was later unlikely to have an ace because of the sequence of cards and actions postflop. Our hand was too strong in many ways, and that meant betting small.

Learn to recognize these spots and size your bets accordingly. When trying to get the crying call, you'll sometimes happily get the moping check-raise shove.